indicator

6032 EN.ATM.CO2E.PC

6048 EN.ATM.METH.PC

6059 EN.ATM.NOXE.PC

name

6032 CO2 emissions (metric tons per capita)

6048 Methane emissions (kt of CO2 equivalent per capita)

6059 Nitrous oxide emissions (metric tons of CO2 equivalent per capita)Quantitative Methods Bootcamp

2023-09-27

Before We Start

Download:

- The slides for this bootcamp

- The dataset we will use (“WDI_Data.dta”)

Make sure to save the dataset in an easy-to-access folder

- A place you can also access from elsewhere (e.g., N-drive)

Objectives of This Bootcamp

Overarching goal

Be on common starting point + ready to take on the quantitative MSc modules

- Refresh key statistical concepts

- E.g., sampling distributions, hypothesis testing

- Obtain basic familiarity with R & Stata

Statistical Inference

Statistical inference is used to learn from incomplete data

We wish to learn some characteristics of a population (e.g., the mean and standard deviation of the heights of all women in the UK), which we must estimate from a sample or subset of that population

Two types of inference:

- Descriptive inference: What is going on, or what exists?

- Causal inference: Why is something going on, why does it exist? Does X cause Y?

Example data

The code below loads the WDI packages and searches for an indicator on CO2 per capita. It uses the statistics software R (more later).

The code below uses the WDI API to retrieve the data and creates a dataframe of three indicators.

# Define countries, indicators form above, and time period

wd.df <- WDI(country = "all",

indicator = c('population' = "SP.POP.TOTL",

'gdp_pc' = "NY.GDP.PCAP.KD",

'co2_pc' = "EN.ATM.CO2E.PC"),

extra = TRUE,

start = 2019, end = 2019)

# Drop all country aggregrates

wd.df <- wd.df[which(wd.df$region != "Aggregates"), ]

# Save data

save(wd.df, file = "WDI_short.RData")Descriptive Inference

expand for full code

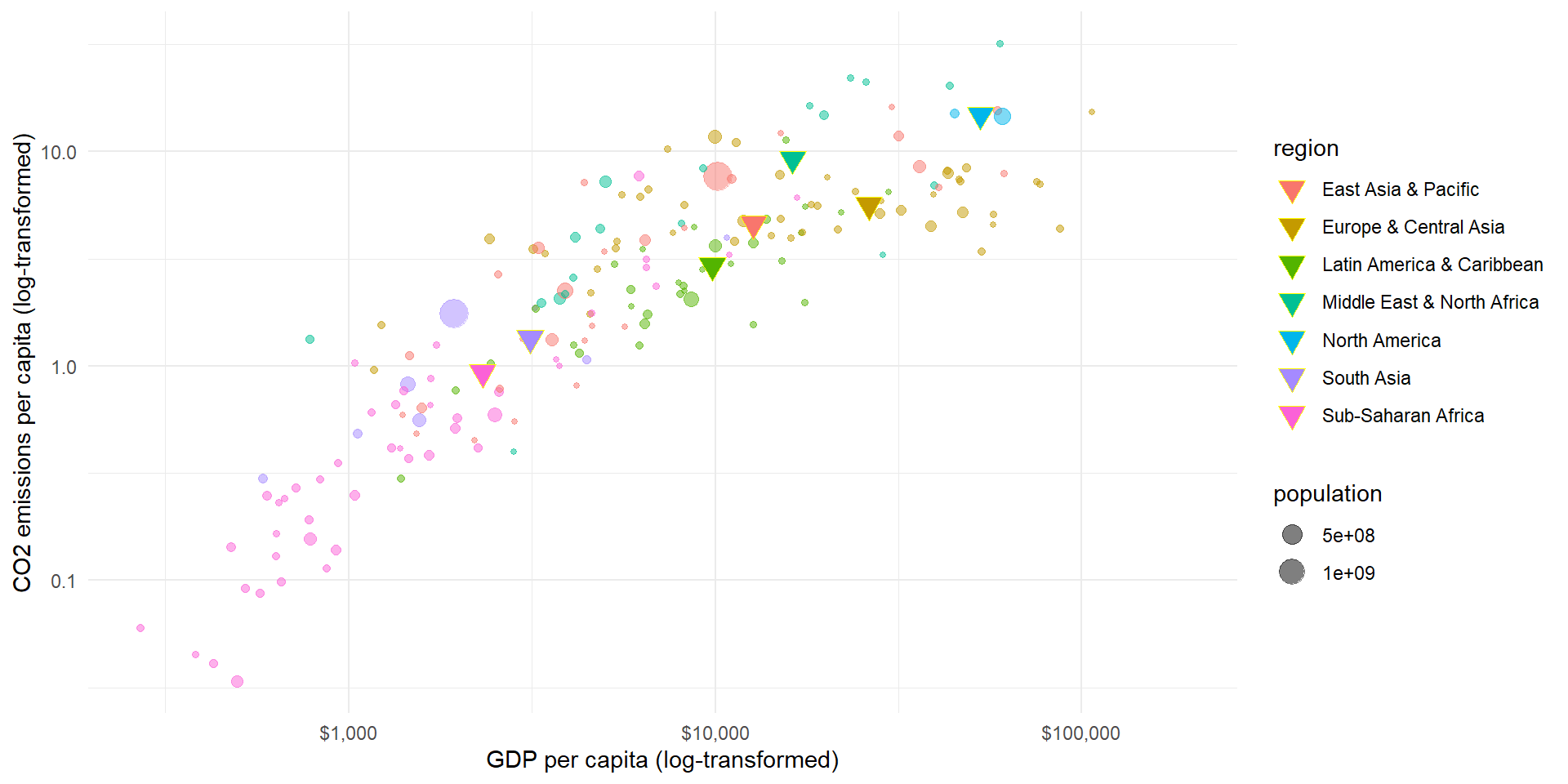

library(ggplot2)

pl <- ggplot(wd.df, aes(x = gdp_pc, y = co2_pc, size = population, color = region)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.5) +

theme_minimal() + scale_y_log10() + scale_x_log10(labels = scales::dollar_format()) +

labs(y = "CO2 emissions per capita (log-transformed)", x = "GDP per capita (log-transformed)")

pl

Descriptive: What are the average CO2 emissions of all European countries?

Descriptive Inference

What are the average CO2 emissions of all European countries?

Mean by region

mean_co2 <- mean(wd.df$co2_pc[which(wd.df$region == "Europe & Central Asia")],

na.rm = TRUE)

mean_co2[1] 5.608387This is the average across European countries.

Why is it not the average across all Europeans?

Descriptive Inference

What are the average CO2 emissions of all European countries?

Code

# Create group means (only for complete observations)

tmp.df <- wd.df[, c("region", "gdp_pc", "co2_pc")]

tmp.df <- tmp.df[complete.cases(tmp.df),]

means.df <- aggregate(tmp.df[, c("gdp_pc", "co2_pc")],

by = list(region = tmp.df$region),

FUN = function(x) mean(x, na.rm = TRUE))

# Plot

pl_mean <- ggplot(wd.df, aes(x = gdp_pc, y = co2_pc, color = region)) +

geom_point(data = wd.df, mapping = aes(x = gdp_pc, y = co2_pc, size = population, color = region),

alpha = 0.5) +

geom_point(data = means.df,

mapping = aes(x = gdp_pc, y = co2_pc, fill = region),

size = 4, shape = 25, color = "yellow") +

theme_minimal() + scale_y_log10() + scale_x_log10(labels = scales::dollar_format()) +

labs(y = "CO2 emissions per capita (log-transformed)", x = "GDP per capita (log-transformed)")

pl_mean

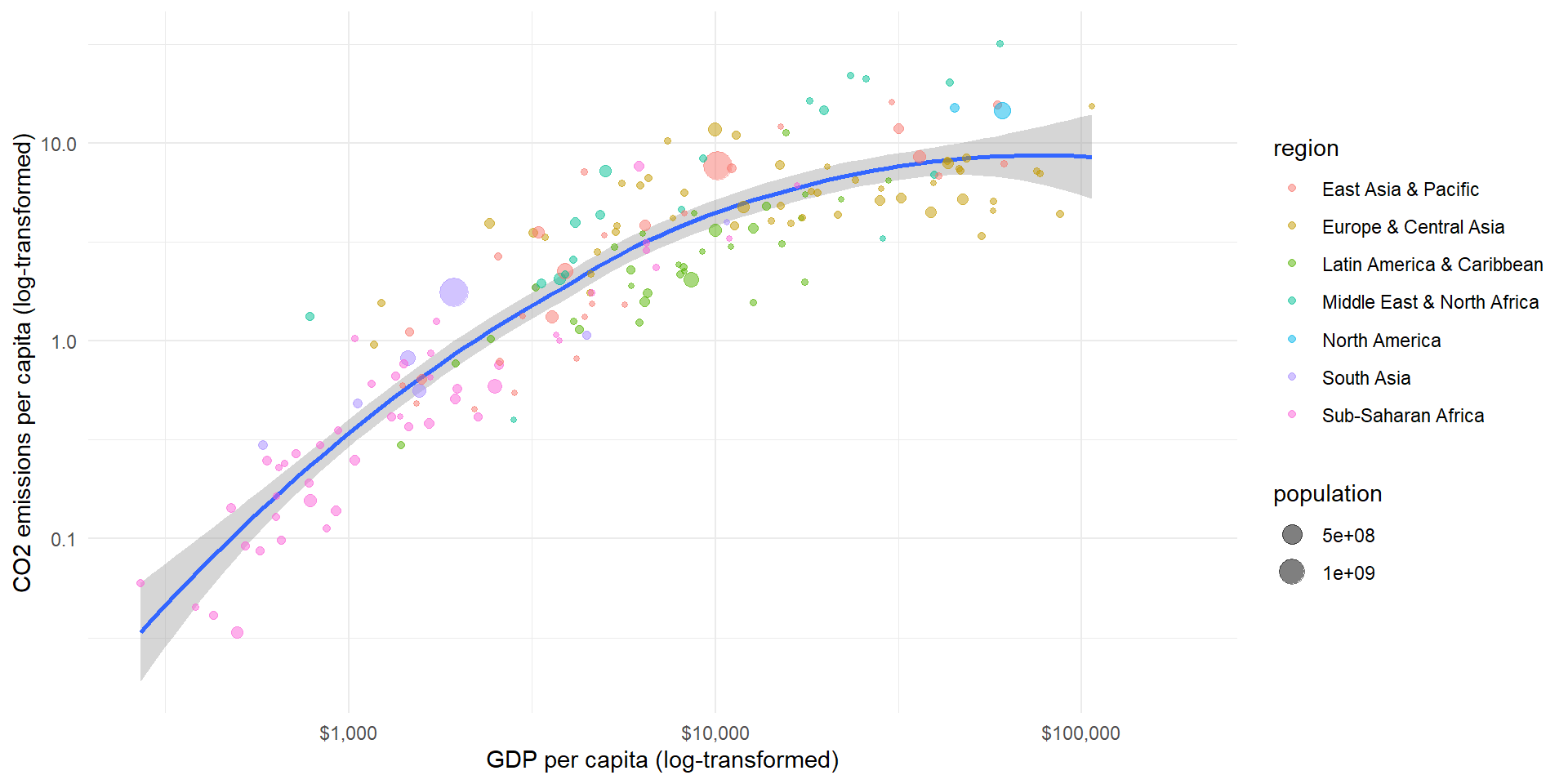

Causal Inference

expand for full code

pl2 <- ggplot(wd.df, aes(x = gdp_pc, y = co2_pc, size = population, color = region)) +

geom_smooth(aes(group = 1), show.legend = "none") + geom_point(alpha = 0.5) +

theme_minimal() + scale_y_log10() + scale_x_log10(labels = scales::dollar_format()) +

labs(y = "CO2 emissions per capita (log-transformed)", x = "GDP per capita (log-transformed)")

pl2

Causal: How does GDP influence the amount of CO2 emissions?

Variables and Observations

A variable is anything that can vary across units of analysis: it is a characteristic that can have multiple values

- E.g., sex, age, diameter, financial revenue, temperature

A unit of analysis is the major entity that you analyse

- E.g., individuals, objects, schools, countries

An observation is the value of a particular variable for a particular unit (sometimes a unit is in its entirety referred to as observation)

- E.g., the individual King Charles III is 73 years of age

Different Types of Variables

Continuous / interval-ratio variables:

They have an ordering, they can take on infinitely many values, and you can do calculations with them

- E.g., income, age, weight, minutes

Categorical variables:

Each observation belongs to one out of a fixed number of categories

- Ordinal variables: there is a natural ordering of the categories

- Nominal variables: there is no natural ordering of the categories

- E.g., education level, Likert scales, gender, vote choice

Describing variables

Decribing variables

Describing data is necessary because there is usually too much of it, so it does not make any sense to look at every data point

We thus have to look for ways to summarize central tendencies, variation, and relationships that exist in the data

There are many different ways to do this

- Visual depictions

- Numerical descriptions

- E.g. mean, mode, median, standard deviation

Distribution

Variables can be characterized by their frequency distribution:

The distribution of the (relative) frequencies of their values

- E.g., we can graph the world income distribution:

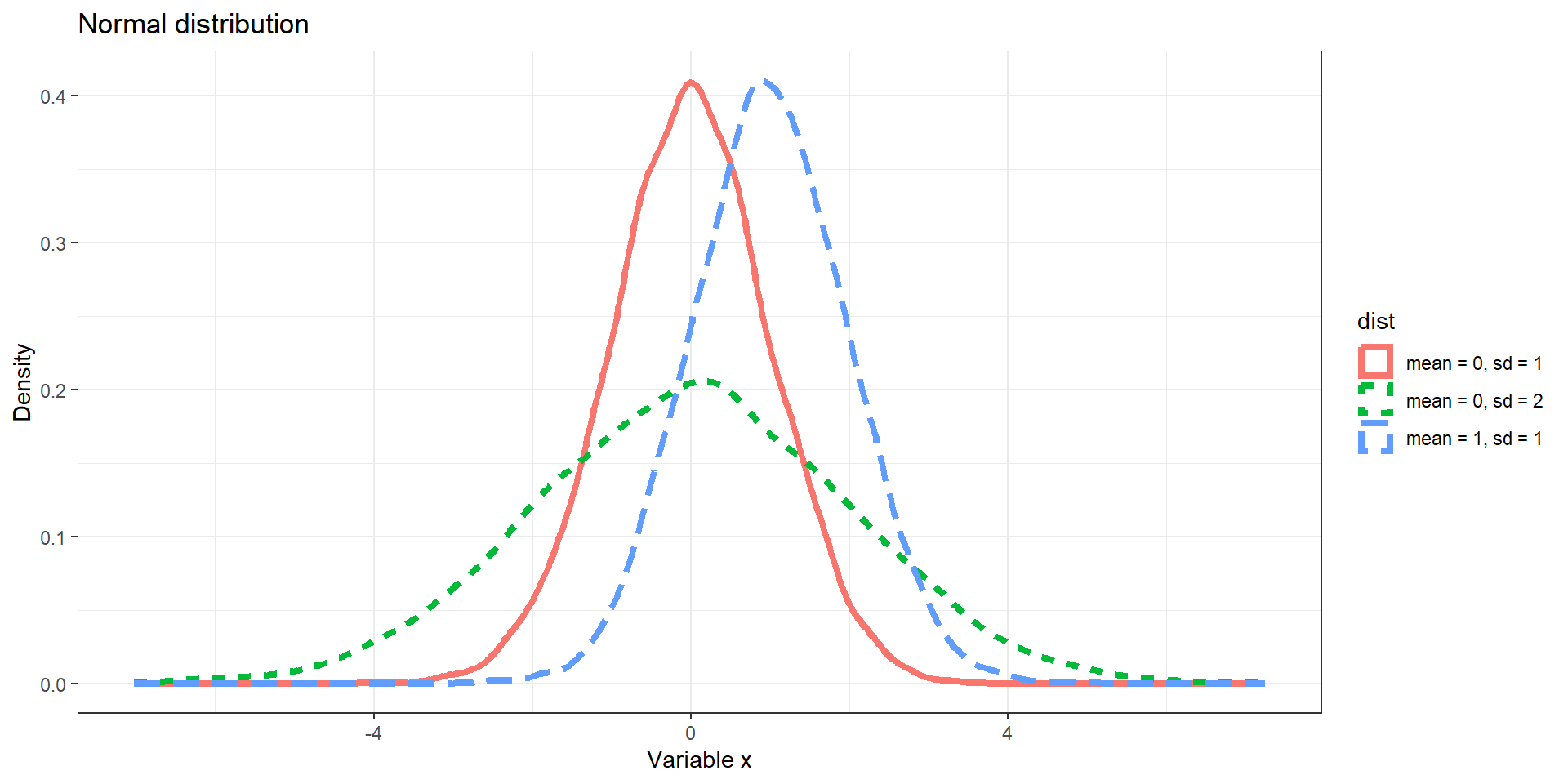

Distributions: Examples

- Normal distribution

- Chi-squared distribution

Distributions: Example I

expand for full code

# Seed for random number

set.seed(12345)

# Normal distribution

d1 <- data.frame(x = rnorm(10000, 0, 1), dist = "mean = 0, sd = 1")

d2 <- data.frame(x = rnorm(10000, 1, 1), dist = "mean = 1, sd = 1")

d3 <- data.frame(x = rnorm(10000, 0, 2), dist = "mean = 0, sd = 2")

p <- ggplot(rbind(d1, d2, d3), aes(x = x)) +

geom_density(aes(color = dist, linetype = dist), size = 1.5) +

labs(y = "Density", x = "Variable x") + theme_bw() +

ggtitle("Normal distribution")

p

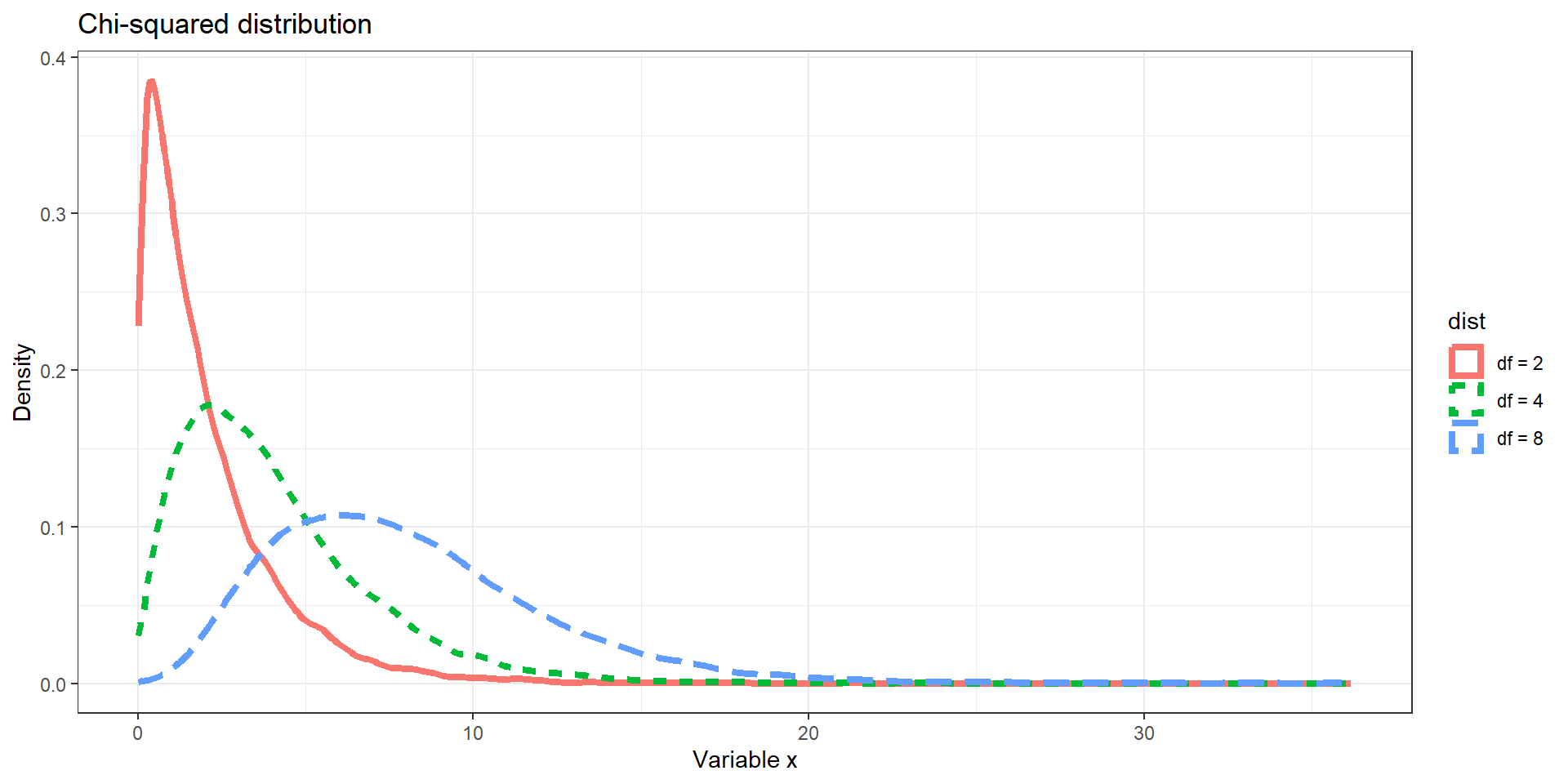

Distributions: Example II

expand for full code

# Chi Squared distribution

d2 <- data.frame(x = rchisq(10000, 2), dist = "df = 2")

d3 <- data.frame(x = rchisq(10000, 4), dist = "df = 4")

d4 <- data.frame(x = rchisq(10000, 8), dist = "df = 8")

p <- ggplot(rbind(d2, d3, d4), aes(x = x)) +

geom_density(aes(color = dist, linetype = dist), size = 1.5) +

labs(y = "Density", x = "Variable x") + theme_bw() +

ggtitle("Chi-squared distribution")

p

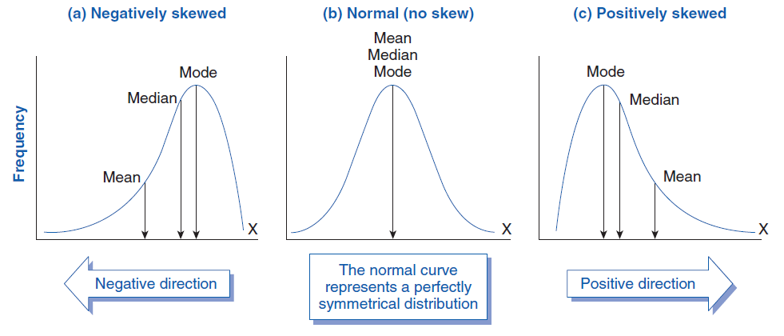

Distributions: Example III

Distributions can take on many different shapes

Measures of Central Tendency

Mean: conventional average calculated by adding all values for all units and dividing by the number of units

\[\overline{x}=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_{i}=\frac{1}{n}\left(x_{1}+\cdots+x_{n}\right), \mathrm{with~units~}i = (1, 2, \dots, n)\]

- May give a distorted impression if there are outliers

Median: value that falls in the middle if we order all units by their value on the variable

Mode: most frequently occurring value across all units

Measures of Dispersion

Variance: average of the squared differences between each observed value on a variable and its mean \[ \sigma^2 = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \bar{x})^2 \]

- Why the square? To treat + and – differences alike

Standard deviation: average departure of the observed values on a variable from its mean

\[ \sigma = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \bar{x})^2} \]

- It is the square root of the variance; it “reverts” the square-taking in the variance calculation, to bring the statistic back to the original scale of the variable

Measures of Dispersion

expand for full code

# Seed for random number

set.seed(12345)

# Normal distribution

d1 <- data.frame(x = rnorm(10000, 0, 0.5), dist = "sd = 0.5")

d2 <- data.frame(x = rnorm(10000, 0, 1), dist = "sd = 1")

d3 <- data.frame(x = rnorm(10000, 0, 3), dist = "sd = 3")

p <- ggplot(rbind(d1, d2, d3), aes(x = x)) +

geom_density(aes(color = dist, linetype = dist), size = 1.5) +

labs(y = "Density", x = "Variable x") + theme_bw() +

ggtitle("Normal distribution") + geom_vline(xintercept = 0)

p

Notation

Typically, we use Roman letters for sample statistics and Greek letters for population statistics:

- Sample mean \(= \bar{x}\) population mean \(= \mu\)

- Sample variance \(= s^2\), population variance \(= \sigma^2\)

- Sample standard error \(= s\), population standard deviation \(= \sigma\)

Recall: the sample is what we observe, the population is what we want to make inferences about

Decribing relationships

Decribing relationships

Often, we are not just interested in the distribution of a single variable. 1

Instead, we are interested in relationships between several variables. If there is a relationship between variable, knowing one variable can tell you something about the other variable.

- Age and height

- GDP and CO2 emissions

- Education and income

Hypothesis testing

A hypothesis is a theory-based statement about a relationship that we expect to observe

- E.g., girls achieve higher scores than boys on reading tests

For every hypothesis there is a corresponding null hypothesis about what we would expect if our theory is incorrect

- E.g., there is no association between Y and X in the population

- In our example: girls are not better readers than boys

Covariance

Covariance refers to the idea that the pattern of variation for one variable corresponds to the pattern of variation for another variable: the two variables “vary together”

Statistically speaking, covariance is the multiplication of the deviations from the mean for the first variables and the deviations from the mean for the second variable:

\[cov_{x,y}=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}(x_{i}-\bar{x})(y_{i}-\bar{y})\]

- The covariance tells us the direction of an association: + or –

- It does not tell us about the strength of the association (reference to underlying distributions of variables is missing)

Pearson’s Correlation

For continuous data, we can calculate Pearson’s correlation (\(\rho\))

- \(\rho\) measures strength & direction of association for linear trends

- \(\rho\) rescales the covariance to the underlying distributions of the variables involved:

\[ \rho = \frac{cov_{x,y}}{\sigma_X \sigma_Y} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n}(x_{i}-\bar{x})(y_{i}-\bar{y})} {\sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \bar{x})^2} \sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - \bar{y})^2}}\]

Dividing the covariance by the product of the standard deviations normalizes the covariance to a range from -1 to +1

- -1 = perfectly negative correlation (all points on decreasing line)

- +1 = perfectly positive correlation (all points on increasing line)

- 0 = no correlation (random cloud of points)

- Correlation is weaker closer to 0 and stronger closer to +/-1

Example I

Example I

Code

# use log transformed variables

wd.df$ln_gdp_pc <- log(wd.df$gdp_pc)

wd.df$ln_co2_pc <- log(wd.df$co2_pc)

# calculate covariance

cov <- cov(wd.df$ln_gdp_pc, wd.df$ln_co2_pc, use = "complete.obs")

# sd

sd_gdp <- sd(wd.df$ln_gdp_pc, na.rm = TRUE)

sd_co2 <- sd(wd.df$ln_co2_pc, na.rm = TRUE)

# correlation

cor <- cor(wd.df$ln_gdp_pc, wd.df$ln_co2_pc, use = "complete.obs")

# Plot with linear line

pl3 <- ggplot(wd.df, aes(x = gdp_pc, y = co2_pc, size = population, color = region)) +

geom_smooth(aes(group = 1), method = 'lm', show.legend = "none") +

geom_point(alpha = 0.5) +

theme_minimal() + scale_y_log10() + scale_x_log10(labels = scales::dollar_format()) +

labs(y = "CO2 emissions per capita (log-transformed)", x = "GDP per capita (log-transformed)") +

ggtitle(paste("Pearsons correlation = ", round(cor, 3)))

pl3

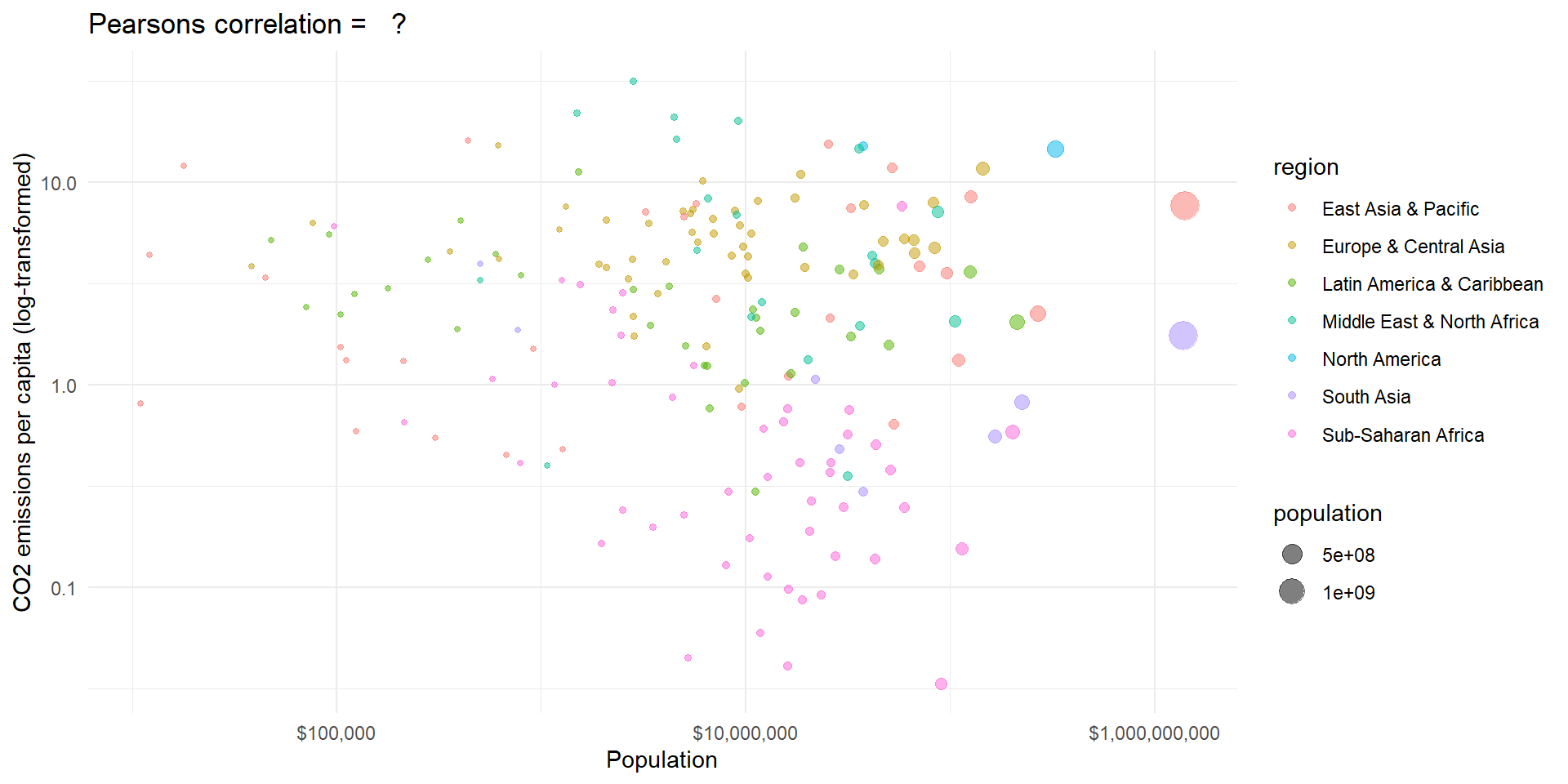

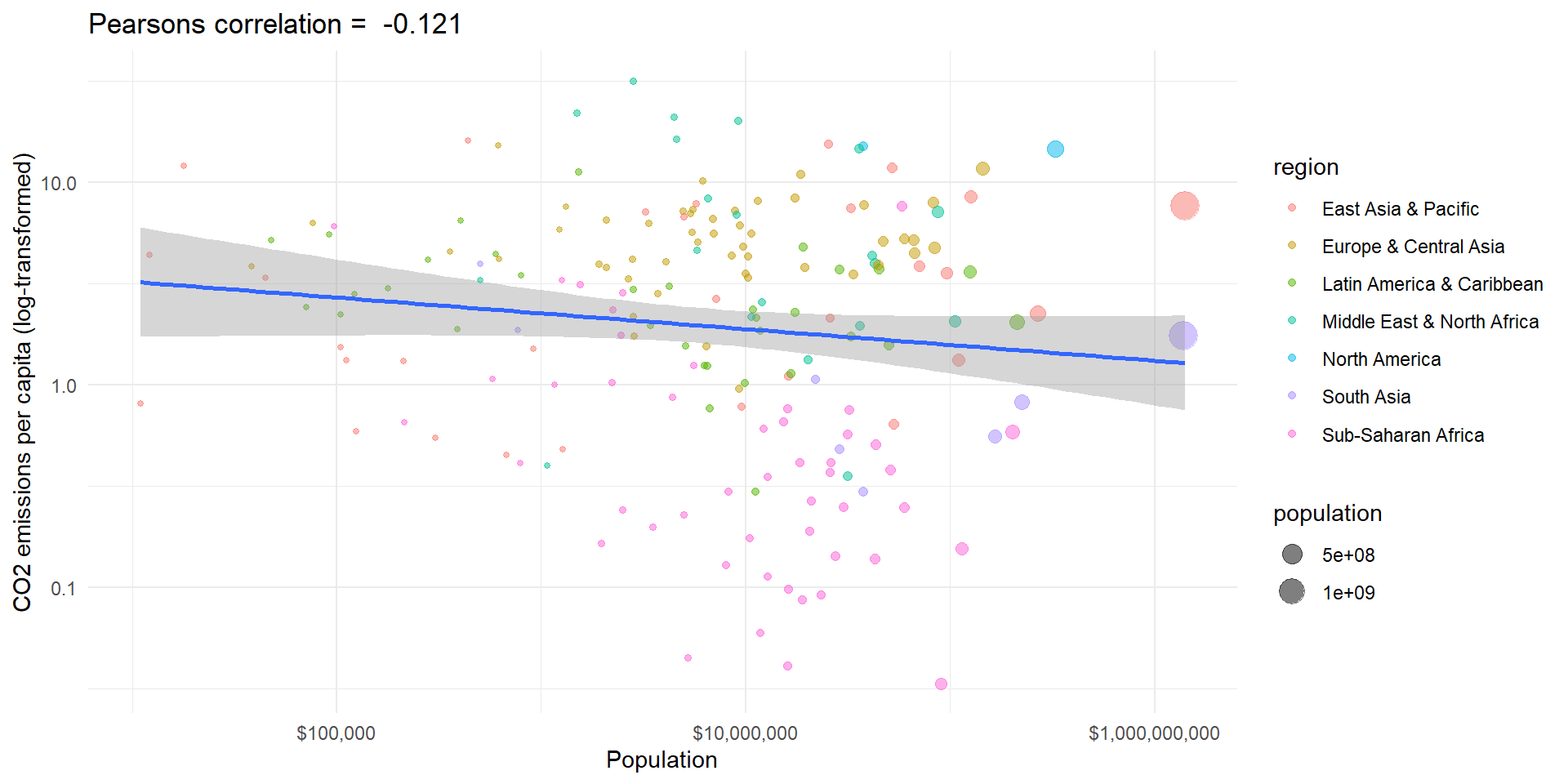

Example II

Code

# use log transformed variables

wd.df$ln_population <- log(wd.df$population)

wd.df$ln_co2_pc <- log(wd.df$co2_pc)

# calculate covariance

cov <- cov(wd.df$ln_population, wd.df$ln_co2_pc, use = "complete.obs")

# sd

sd_gdp <- sd(wd.df$ln_population, na.rm = TRUE)

sd_co2 <- sd(wd.df$ln_co2_pc, na.rm = TRUE)

# correlation

cor <- cor(wd.df$ln_population, wd.df$ln_co2_pc, use = "complete.obs")

# Plot with linear line

pl3 <- ggplot(wd.df, aes(x = population, y = co2_pc, size = population, color = region)) +

# geom_smooth(aes(group = 1), method = 'lm', show.legend = "none") +

geom_point(alpha = 0.5) +

theme_minimal() + scale_y_log10() + scale_x_log10(labels = scales::dollar_format()) +

labs(y = "CO2 emissions per capita (log-transformed)", x = "Population") +

ggtitle(paste("Pearsons correlation = ", " ?"))

pl3

Example II

The world is more complex

The Linear Model

\[ y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{1i} + \beta_2 x_{2i} + \ldots + \beta_k x_{ki} +\epsilon_i \]

- \(y_i\): \(i\) observation \((i = 1, \ldots , n)\) of dependent variable \(y\) ;

- \(X_{ji}\): \(i\) observation of \(j\) explanatory variable \(x\) \((j = 1, \ldots, k)\).

- \(\beta_j\): parameters to be estimated.

- \(\epsilon_i\): error term. It contains all factors affecting \(y_i\), but not contained in \(x_{ji}\).

The OLS estimator

The Omitted Least Squares (OLS) estimator is one way to estimate the parameter \(\beta\) in our population model

To distinguish between estimates and actual parameters to be estimated, the following notation is generally used:

- The estimate for \(\beta\) is indicated as \(\hat\beta\)

- The estimated error term, also called residual is indicated as \(\hat\epsilon\)

- The predicted value of the dependent variable \(y\) is indicated as \(\hat y\)

The OLS estimator

The OLS method chooses the estimates of \(\beta\) to minimise the sum of squared residuals (SSR)

\[ \begin{align} \min_{\beta_0,\dots x\beta_k} [\sum^N_{i=1}(Y_i-\hat Y_i)^2] \quad \text{or} \quad \min_{\beta_0,\dots x\beta_k} [ \hat{\epsilon}^\intercal \hat{\epsilon} ] \end{align} \]

The solution is the OLS estimator: \[ \begin{align} \hat{\beta}_{OLS} = \frac{\sum^N_{i = 1}(X_i - \bar X)(Y_i - \bar Y)}{\sum^N_{i = 1}(X_i - \bar X)^2} \end{align} \]

or in matrix notation: \[ \begin{align} \hat{\mathbf \beta}_{OLS} = (\mathbf X^\intercal \mathbf X)^{-1} \mathbf X^\intercal \mathbf Y \end{align} \]

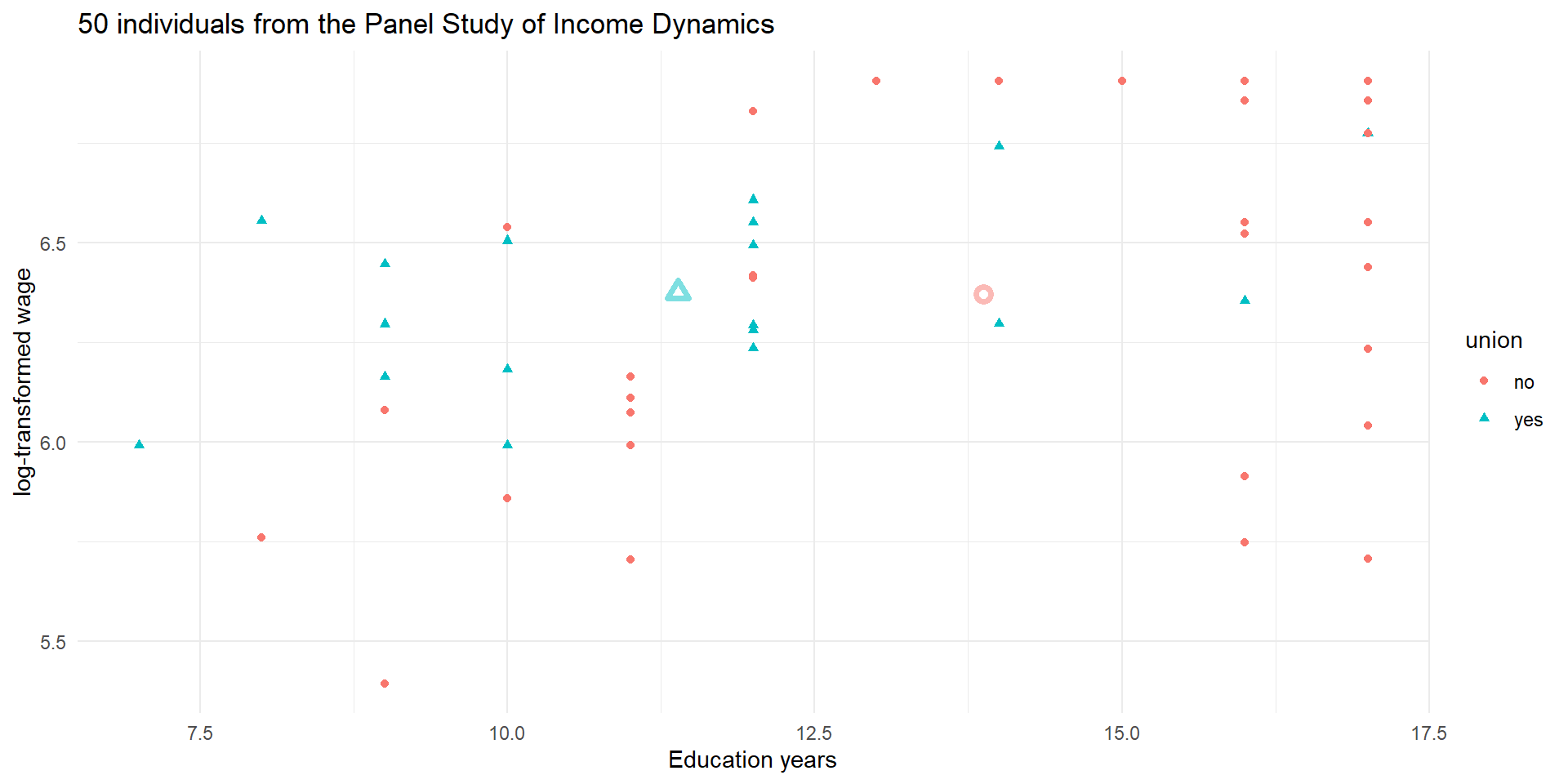

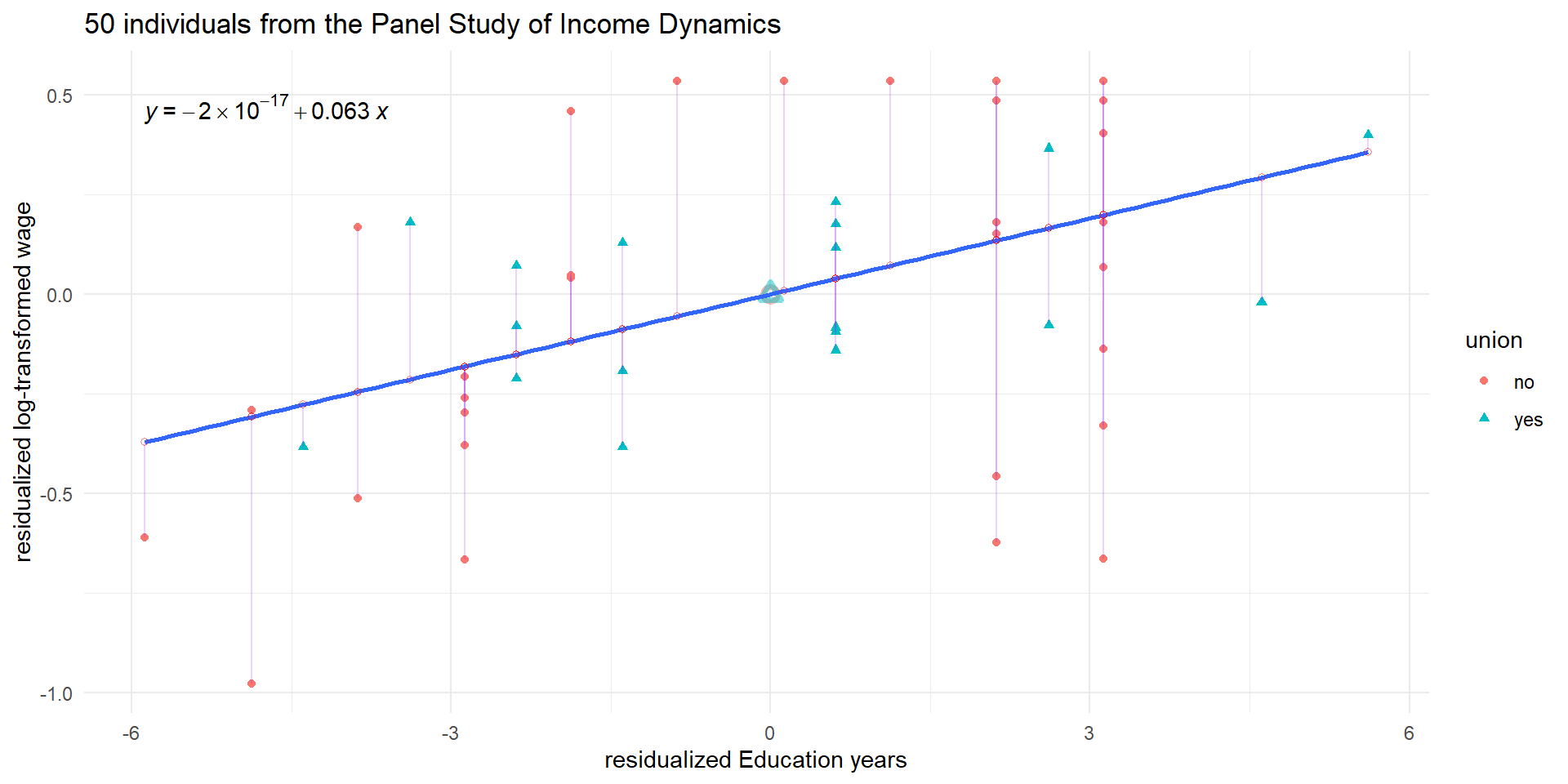

An example: wage

\[ wage_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 education_{i} + \beta_2 union_{i} +\epsilon_i \]

- \(y_i\): log-transformed wage of individual \(i\);

- \(X_{1i}\): education years of individual \(i\).

- \(X_{2i}\): whether or not individual \(i\) is union member.

- \(\epsilon_i\): error term. It contains all factors affecting the wage, but not contained in education years and union membership (such as age, gender, subject, quantitative methods skills, and lots more).

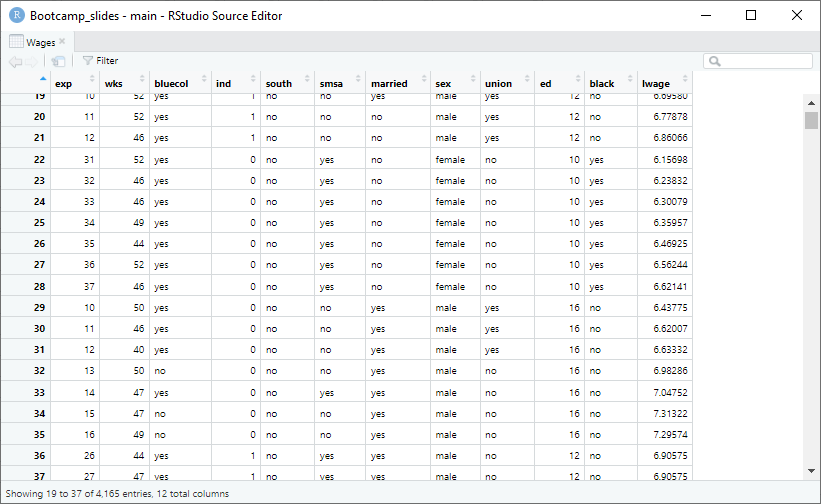

An example: wage

Code

# Get example data

library(plm)

data("Wages")

# Reduce data frame to cross-section

Wages$year <- rep(c(1976:1982), 595)

wages_cs.df <- Wages[which(Wages$year == 1976), ]

# Reduce to 50 individual random sample

set.seed(653210)

wages_cs.df <- wages_cs.df[sample(1:595, 50), ]

# Means

means.df <- aggregate(wages_cs.df[, c("ed", "lwage")],

by = list(union = wages_cs.df$union),

FUN = function(x) mean(x, na.rm = TRUE))

# Plot with linear line

pl3 <- ggplot(wages_cs.df, aes(x = ed, y = lwage, color = union, shape = union)) +

geom_point(alpha = 1) +

geom_point(data = means.df, mapping = aes(color = union),

alpha = 0.5, stroke = 2, size = 2, shape = c(1,2), show.legend = FALSE) +

theme_minimal() +

labs(y = "log-transformed wage", x = "Education years") +

ggtitle("50 individuals from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics")

pl3

An example: wage

The OLS estimator

Call:

lm(formula = lwage ~ ed + union, data = wages_cs.df)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-0.86123 -0.19264 0.01753 0.22068 0.59062

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 5.49218 0.25015 21.956 < 2e-16 ***

ed 0.06330 0.01746 3.626 0.000707 ***

unionyes 0.16195 0.11259 1.438 0.156938

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.3526 on 47 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.2186, Adjusted R-squared: 0.1853

F-statistic: 6.574 on 2 and 47 DF, p-value: 0.003039An example: wage

Code

library(gganimate)

# Residualise y

tmp.mod1 <- lm(lwage ~ union, data = wages_cs.df)

wages_cs.df$lwage_resid <- resid(tmp.mod1)

# Residualise x

tmp.mod1 <- lm(ed ~ union, data = wages_cs.df)

wages_cs.df$ed_resid <- resid(tmp.mod1)

# Create data of states to animate

df <- rbind(data.frame(lwage = wages_cs.df$lwage,

ed = wages_cs.df$ed,

union = wages_cs.df$union,

resid = 0),

data.frame(lwage = wages_cs.df$lwage_resid,

ed = wages_cs.df$ed,

union = wages_cs.df$union,

resid = 1),

data.frame(lwage = wages_cs.df$lwage_resid, # just to duplicate

ed = wages_cs.df$ed,

union = wages_cs.df$union,

resid = 2),

data.frame(lwage = wages_cs.df$lwage_resid,

ed = wages_cs.df$ed_resid,

union = wages_cs.df$union,

resid = 3),

data.frame(lwage = wages_cs.df$lwage_resid, # just to duplicate

ed = wages_cs.df$ed_resid,

union = wages_cs.df$union,

resid = 4),

data.frame(lwage = wages_cs.df$lwage_resid, # just to duplicate

ed = wages_cs.df$ed_resid,

union = wages_cs.df$union,

resid = 5))

means.df <- aggregate(df[, c("lwage", "ed")],

by = list(union = df$union,

resid = df$resid),

FUN = function(x) mean(x, na.rm = TRUE))

# Plot with linear line

pl4 <- ggplot(df, aes(x = ed, y = lwage, color = union, shape = union)) +

geom_point(alpha = 1) +

geom_point(data = means.df,

alpha = 0.5, stroke = 2, size = 2, show.legend = FALSE) +

theme_minimal() +

labs(y = "log-transformed wage", x = "Education years") +

ggtitle("50 individuals from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics")+

transition_states(resid, wrap = FALSE) +

shadow_mark(alpha = 0.7, size = 1)

# + view_zoom(nsteps = 3, include = TRUE,

# look_ahead = 4, wrap = FALSE)

pl4

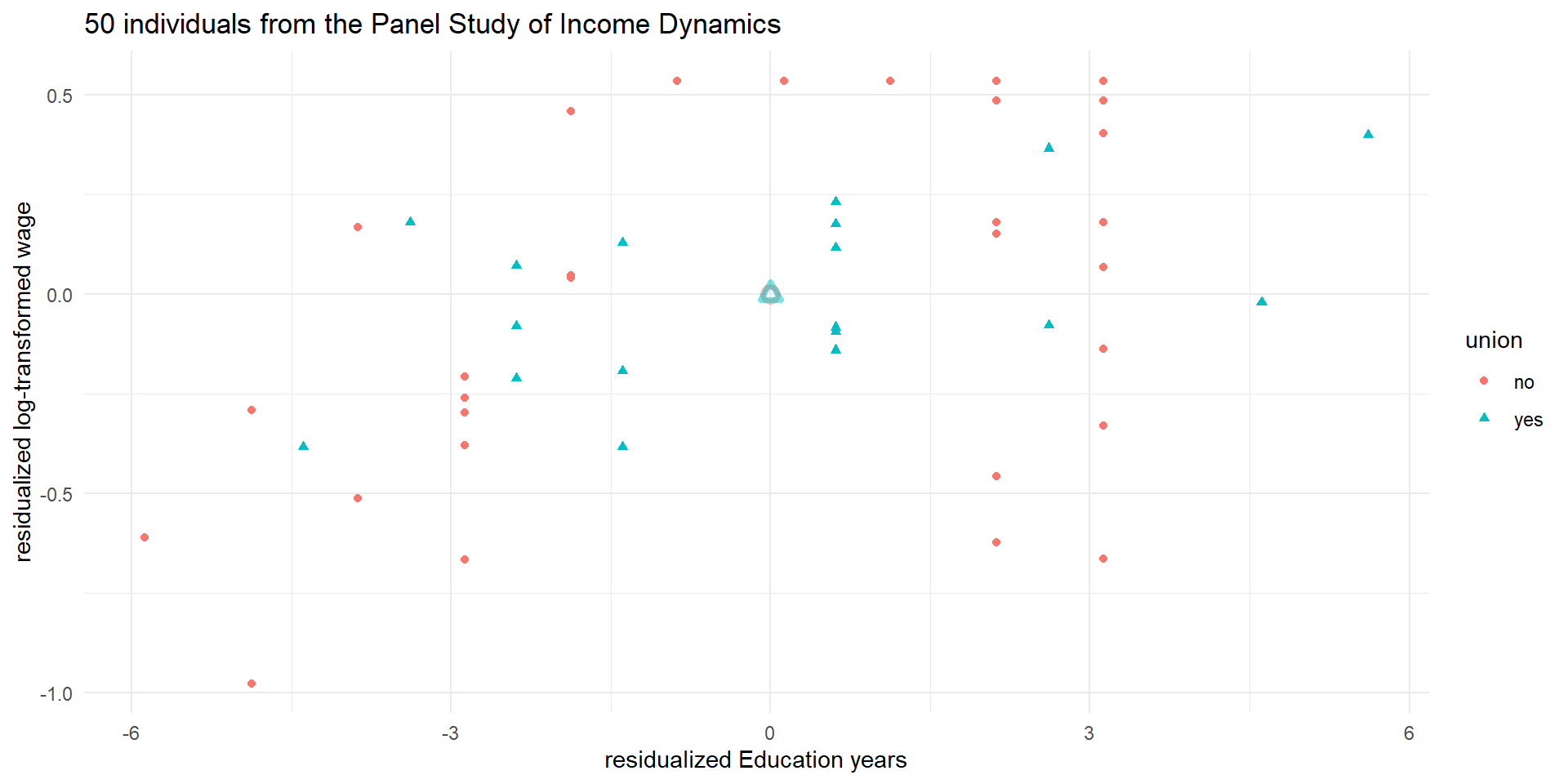

An example: wage

Code

# Means

means.df <- aggregate(wages_cs.df[, c("ed_resid", "lwage_resid")],

by = list(union = wages_cs.df$union),

FUN = function(x) mean(x, na.rm = TRUE))

# Plot with linear line

pl5_0 <- ggplot(wages_cs.df, aes(x = ed_resid, y = lwage_resid)) +

geom_point(aes(color = union, shape = union), alpha = 1) +

geom_point(data = means.df, mapping = aes(color = union),

alpha = 0.5, stroke = 2, size = 2, shape = c(1,2), show.legend = FALSE) +

theme_minimal() +

labs(y = "residualized log-transformed wage", x = "residualized Education years") +

ggtitle("50 individuals from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics")

pl5_0

An example: wage

Code

# fit the model

fit <- lm(lwage_resid ~ ed_resid, data = wages_cs.df)

# Save the predicted values

wages_cs.df$predicted <- predict(fit)

# Save the residual values

wages_cs.df$residuals <- residuals(fit)

library(ggpubr)

# Plot with linear line

pl5 <- ggplot(wages_cs.df, aes(x = ed_resid, y = lwage_resid)) +

geom_point(aes(color = union, shape = union), alpha = 1) +

geom_point(data = means.df, mapping = aes(color = union),

alpha = 0.5, stroke = 2, size = 2, shape = c(1,2), show.legend = FALSE) +

geom_smooth(aes(group = 1), method = 'lm', show.legend = "none", se = FALSE) +

geom_segment(aes(xend = ed_resid, yend = predicted), alpha = .2, color = "purple") +

geom_point(aes(x = ed_resid, y = predicted), alpha = 0.5, shape = 1, color = "red") +

theme_minimal() +

labs(y = "residualized log-transformed wage", x = "residualized Education years") +

ggtitle("50 individuals from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics") +

stat_regline_equation(aes(label = ..eq.label..))

pl5

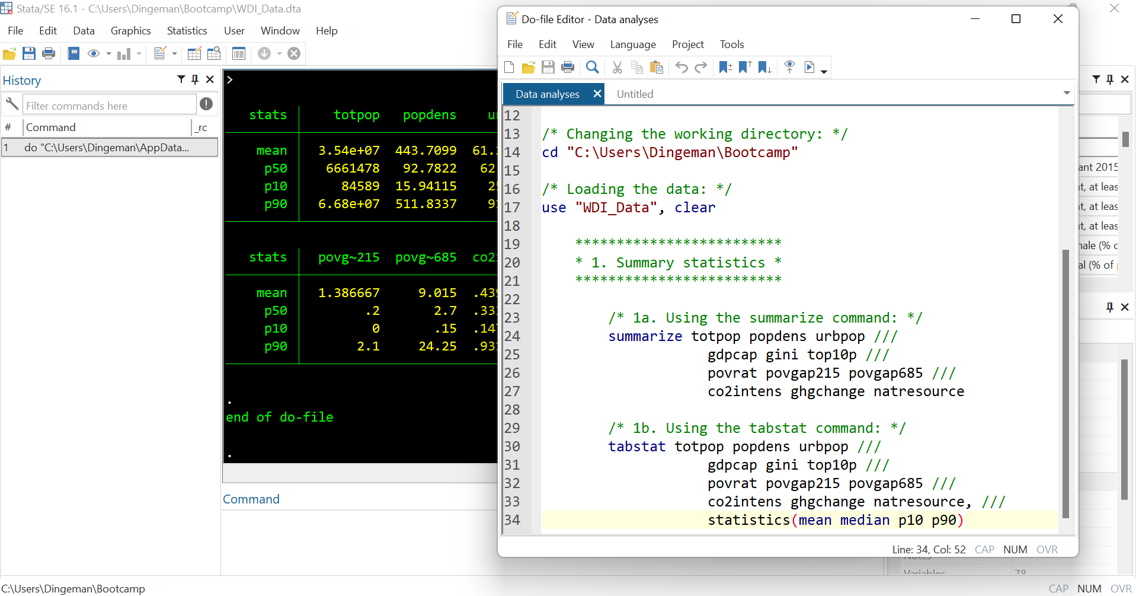

Statistical Software

UCL Download centre

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/isd/services/software-hardware/software-for-students

Statistical software

Stata & R are powerful software packages that allows you to do:

- Data management and manipulation

- Data visualization

- Statistical analysis

- (Writing papers and presentations)

Writing Stata syntax files and R script facilitates reproducibility

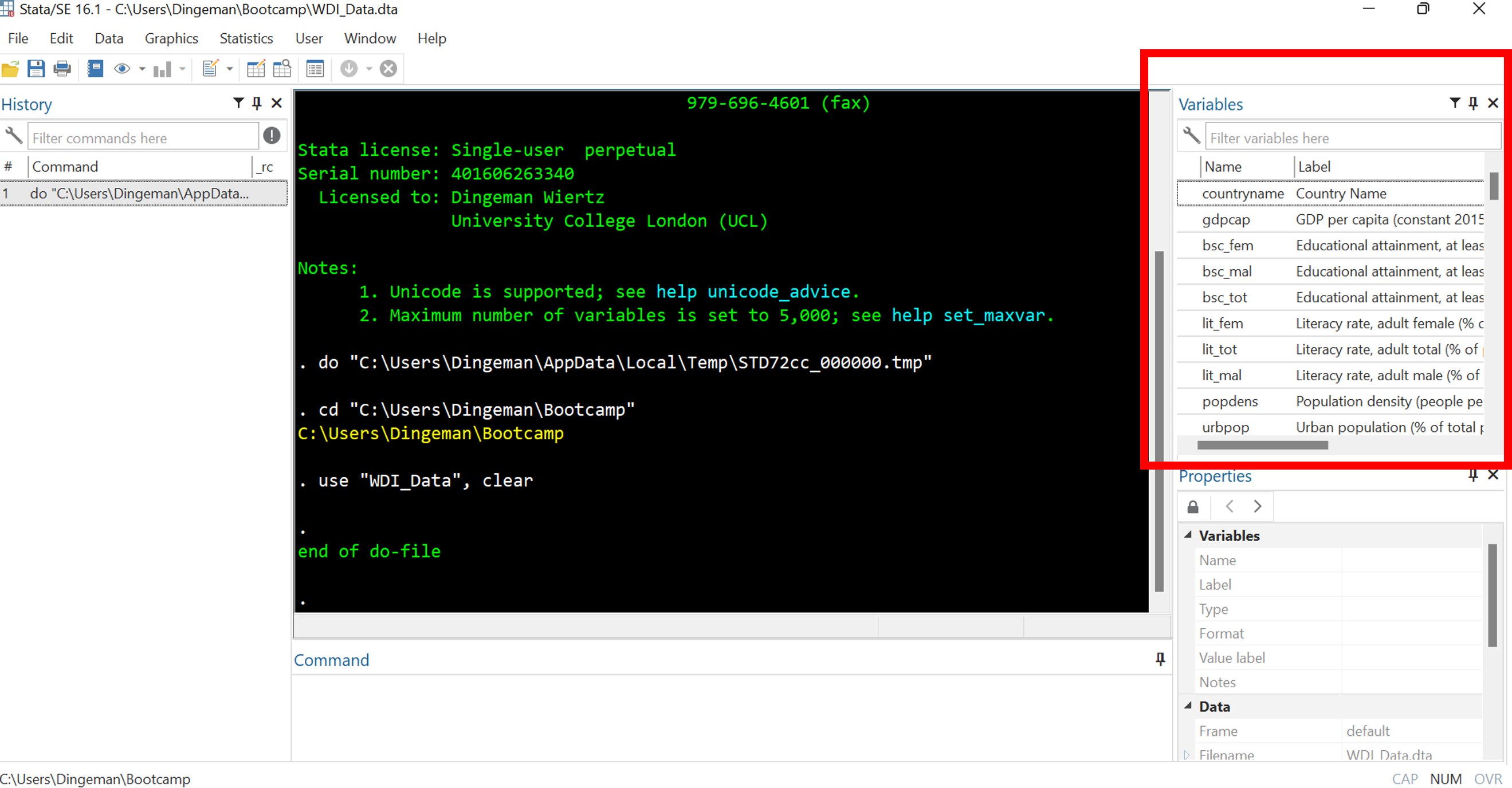

Stata’s Interface: Variables Window

The variables window displays all variables in your dataset

- Single click on variable names to see details in properties window

- Double click to make variables appear in command window

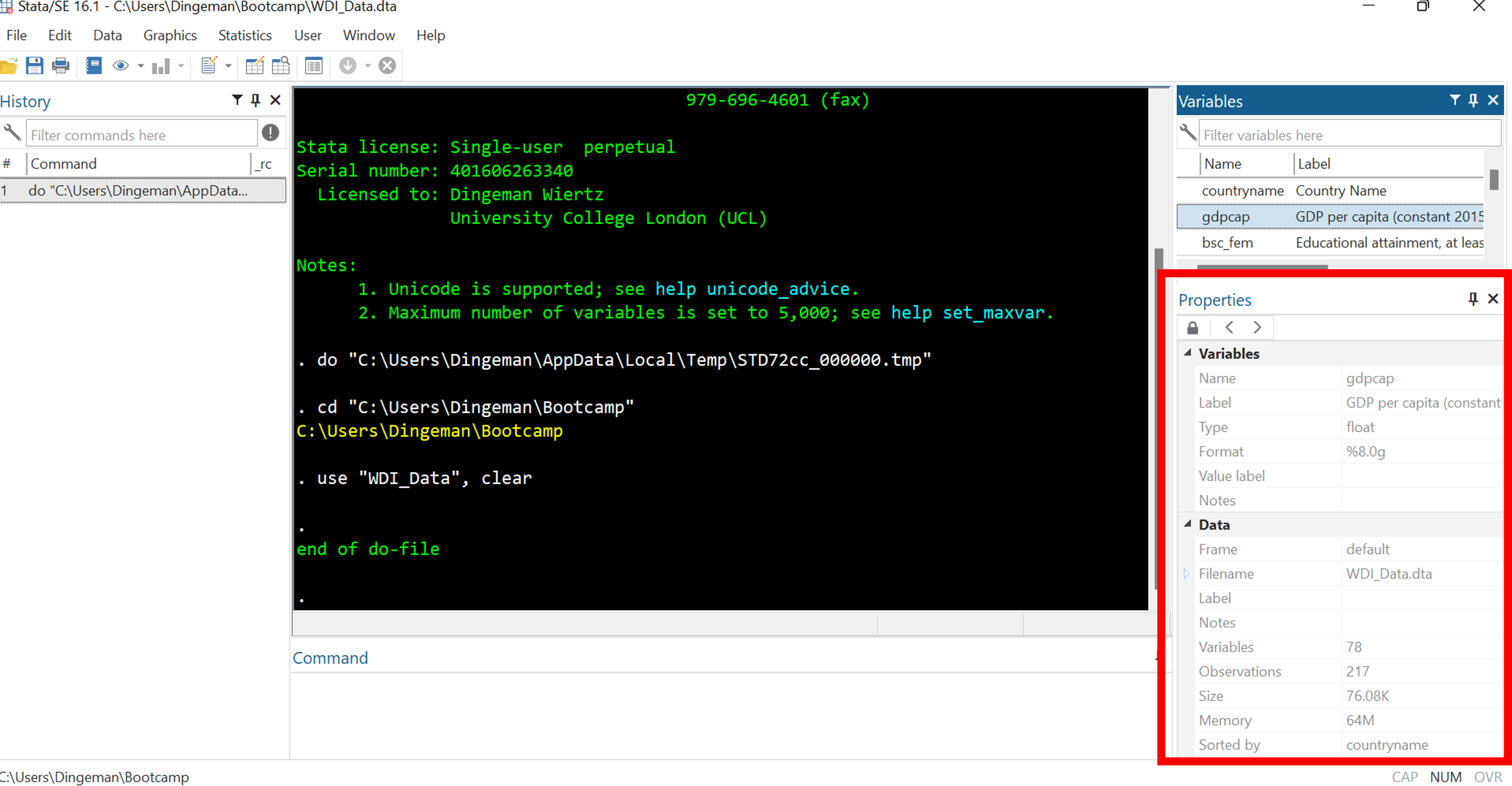

Stata’s Interface: Properties Window

The variables window displays all variables in your dataset

The properties window displays details about selected variables as well as the entire dataset (e.g., number of observations, sort order)

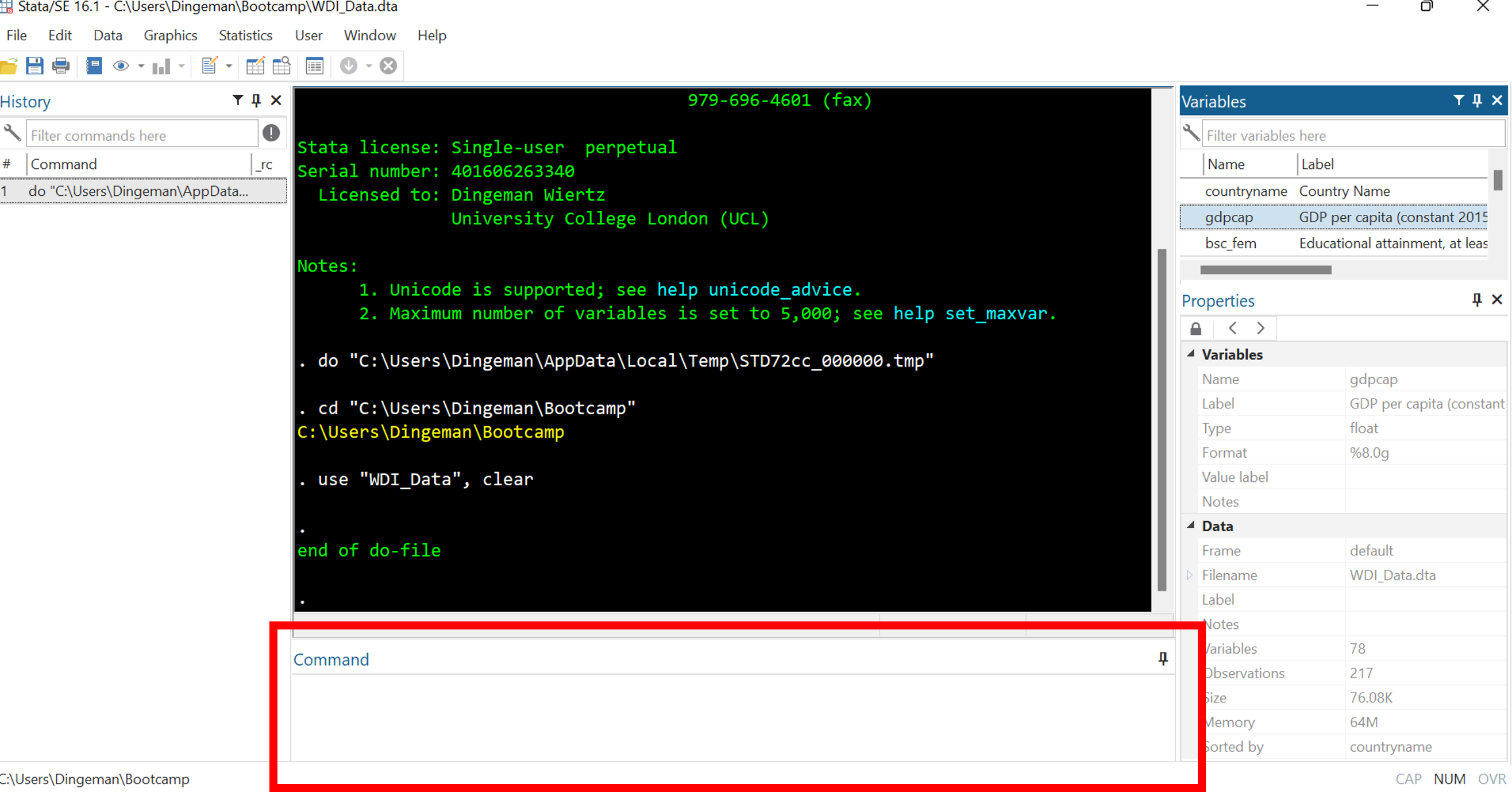

Stata’s Interface: Command Window

The command window is for entering and executing commands

- But it is better to use do-files (same applies to drop-down menus)

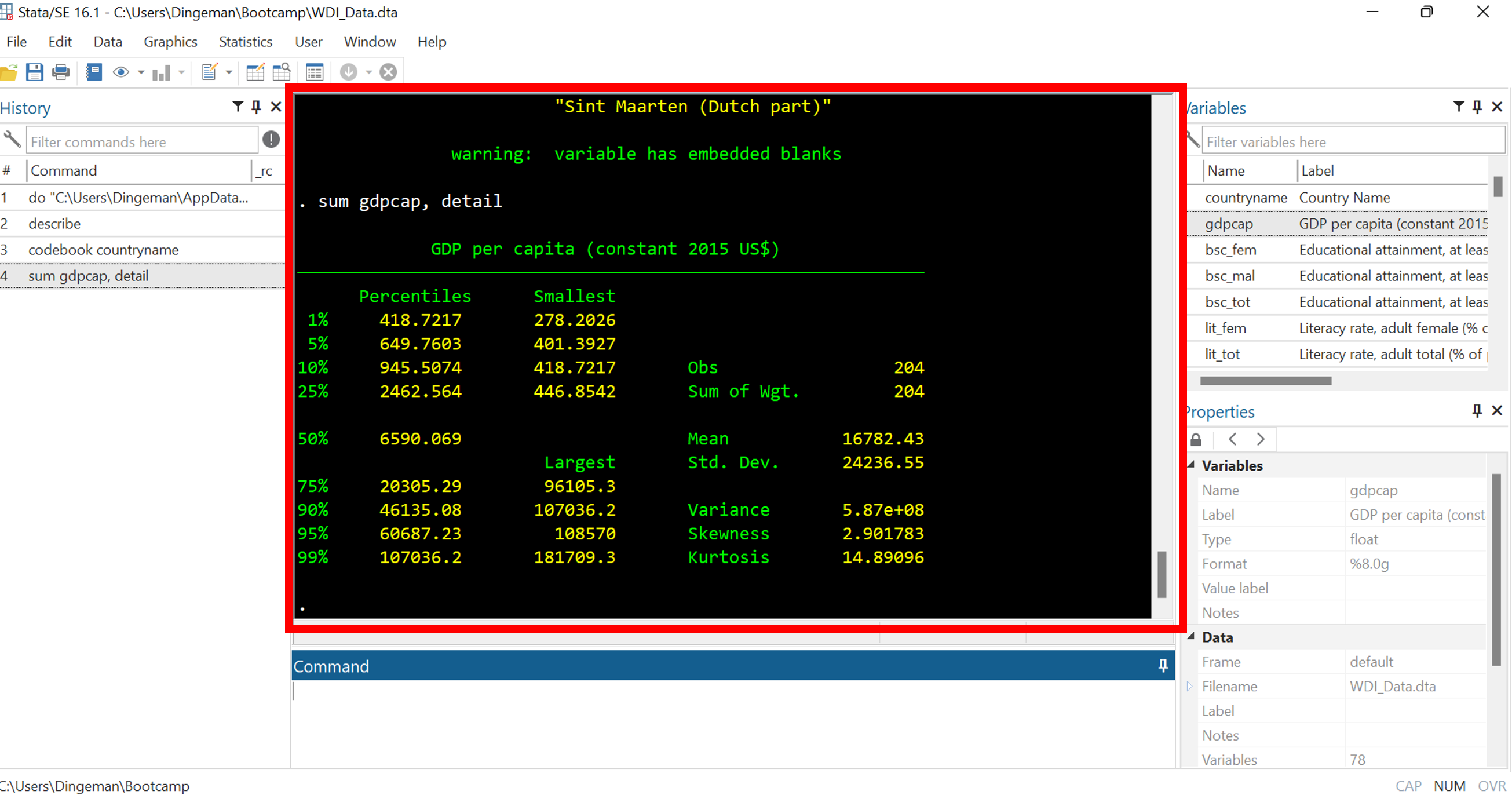

Stata’s Interface: Results Window

The results window displays all output of your commands

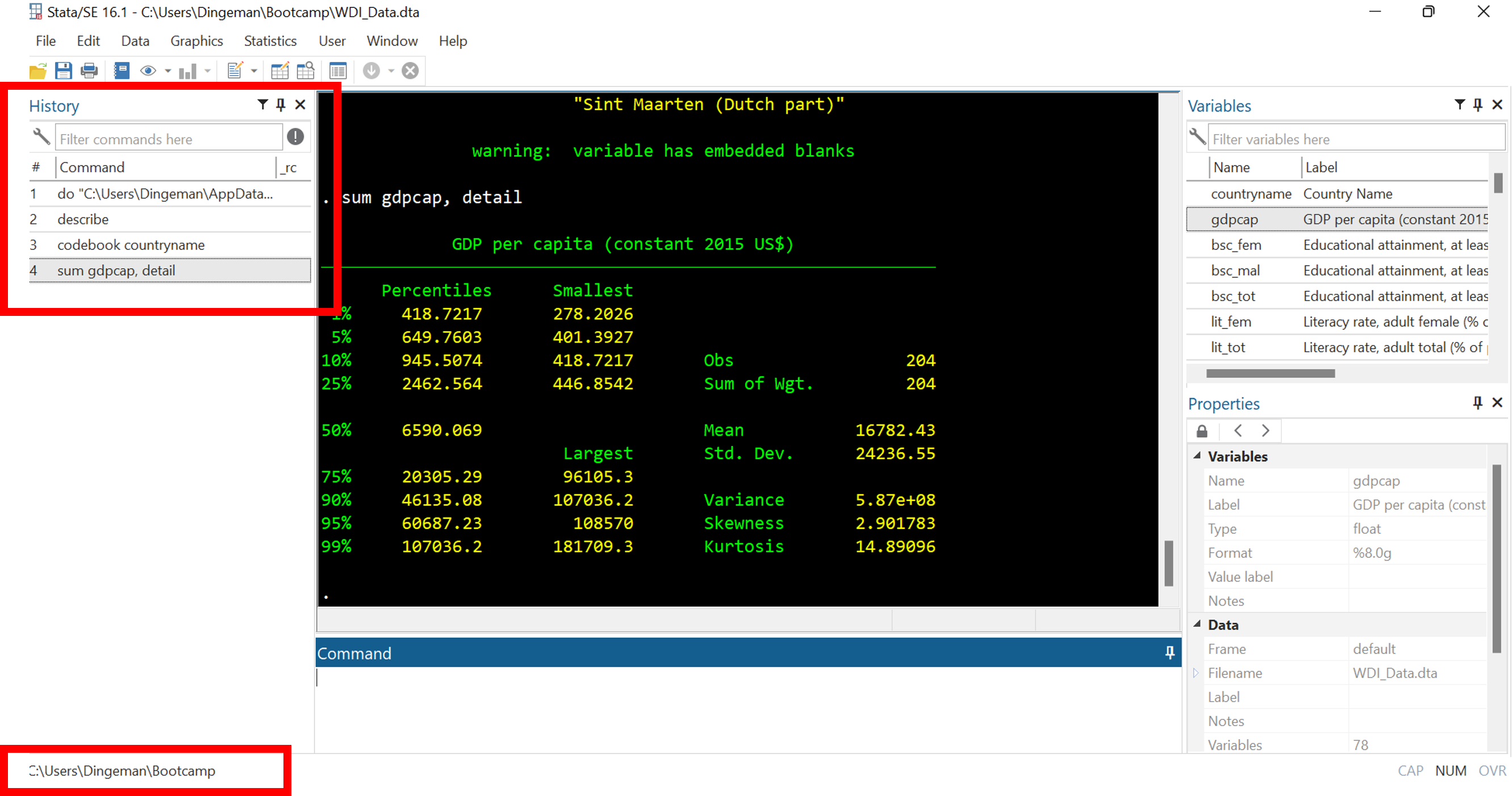

Stata’s Interface: Command History and Current Working Directory

The command history window lists previously run commands

- At the bottom you can see the current working directory: the folder where any files will be loaded from and saved to

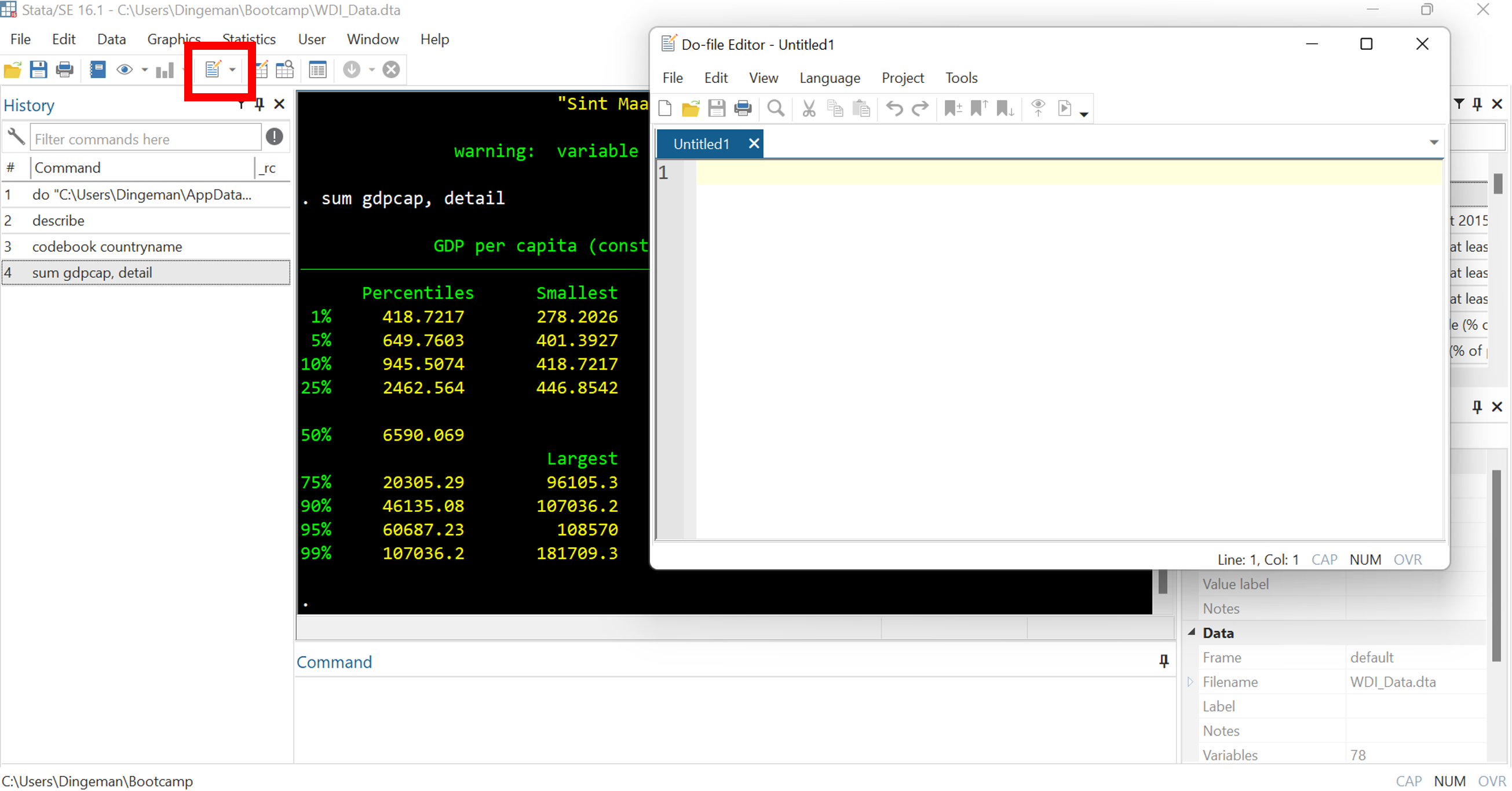

Stata’s Interface: Opening a Do File

Do files are text files where you can store commands for reuse

- Huge payoffs for reproducibility, debugging, adapting commands

Running Commands from a Do File

After entering a command, you select it, and then click the “execute” button or press “Ctrl+D”

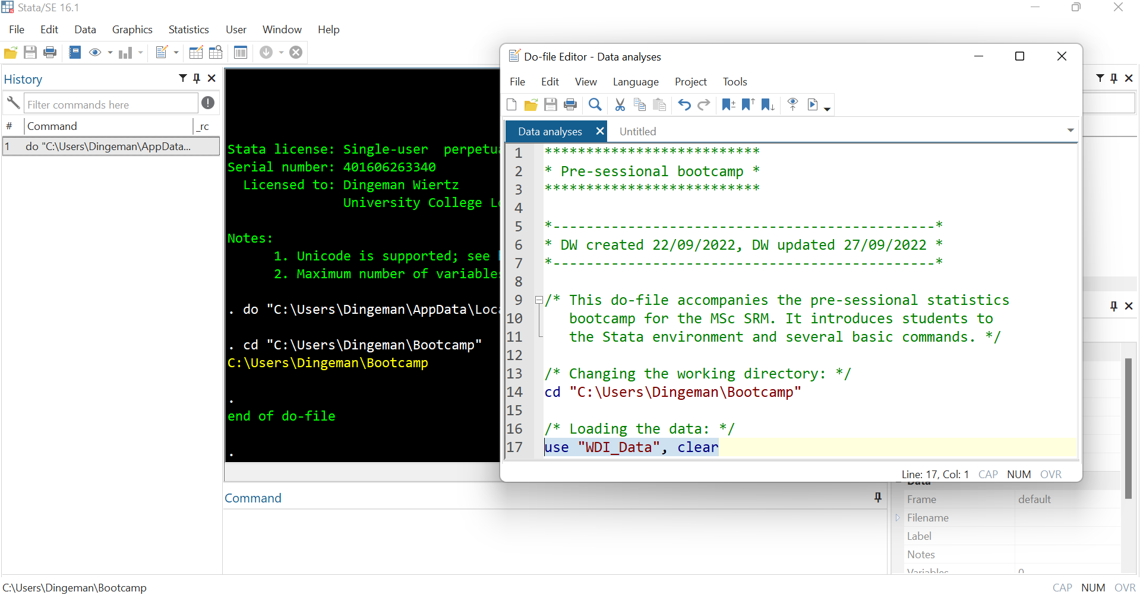

Do File Dos and Don’ts

- Use annotations to facilitate replicability (incl. for future self!):

- Use * for single-line comments and /* */ for multiple lines

Do File Dos and Don’ts

- Break down code into clearly labelled sections / subsections

- Use tab indentations to making things easy to read

Do File Dos and Don’ts

- Don’t put too much information on a single line

- Use /// to continue your command on the next line and

- write “top-to-bottom” instead of “left-to-right”

R & R Studio Interface

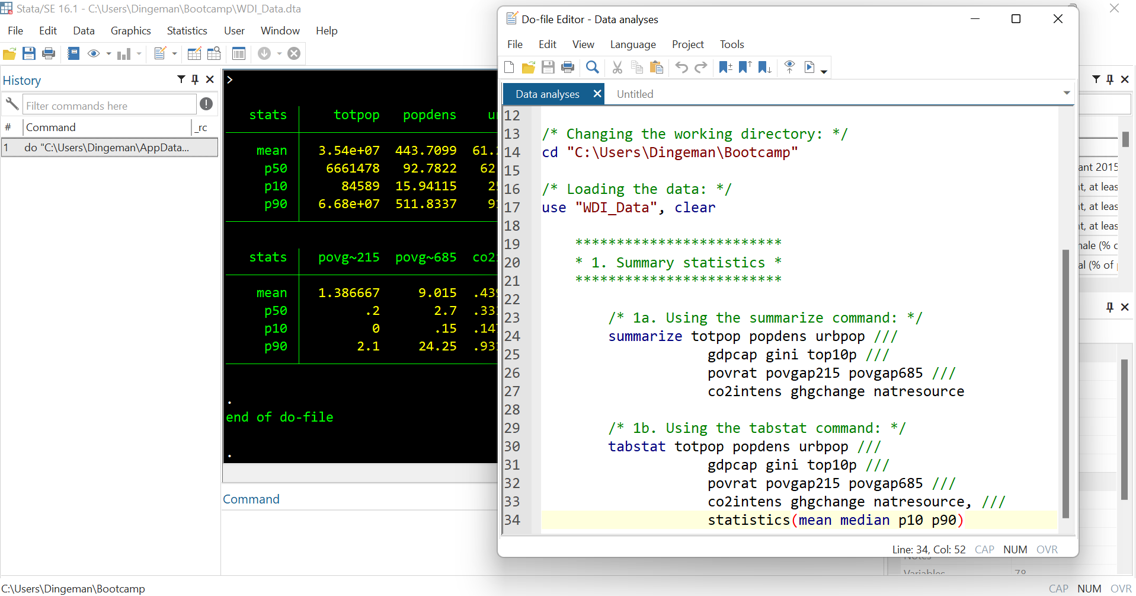

Structure of Commands in Stata

General Stata Command Syntax

Stata commands mirror everyday commands in their structure:

- They often start with a verb: “Bring me…”

- They then list an object: “… a pint of milk…”

- They may add a condition: “… if it is still before noon…”

- They may specify further details after the comma: “, quickly please” or “, I want semi-skimmed”

In nearly all cases, Stata syntax consists of four parts:

- Command: What action do you want to see performed?

- Names of variables, files, objects: On what objects is the command to be performed (“varlist”)

- Qualifier(s) on observations: Which observations are to be taken into account (and how)? (“if”, “in”, “weight”)

- Options: What special things should be done in the execution?

“help [command]” is your friend

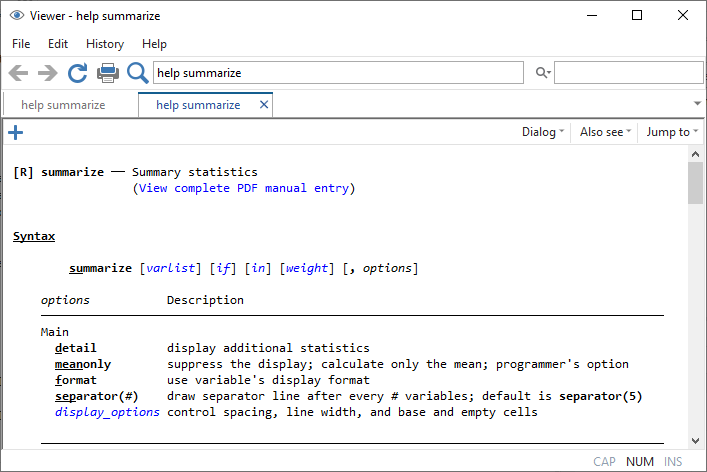

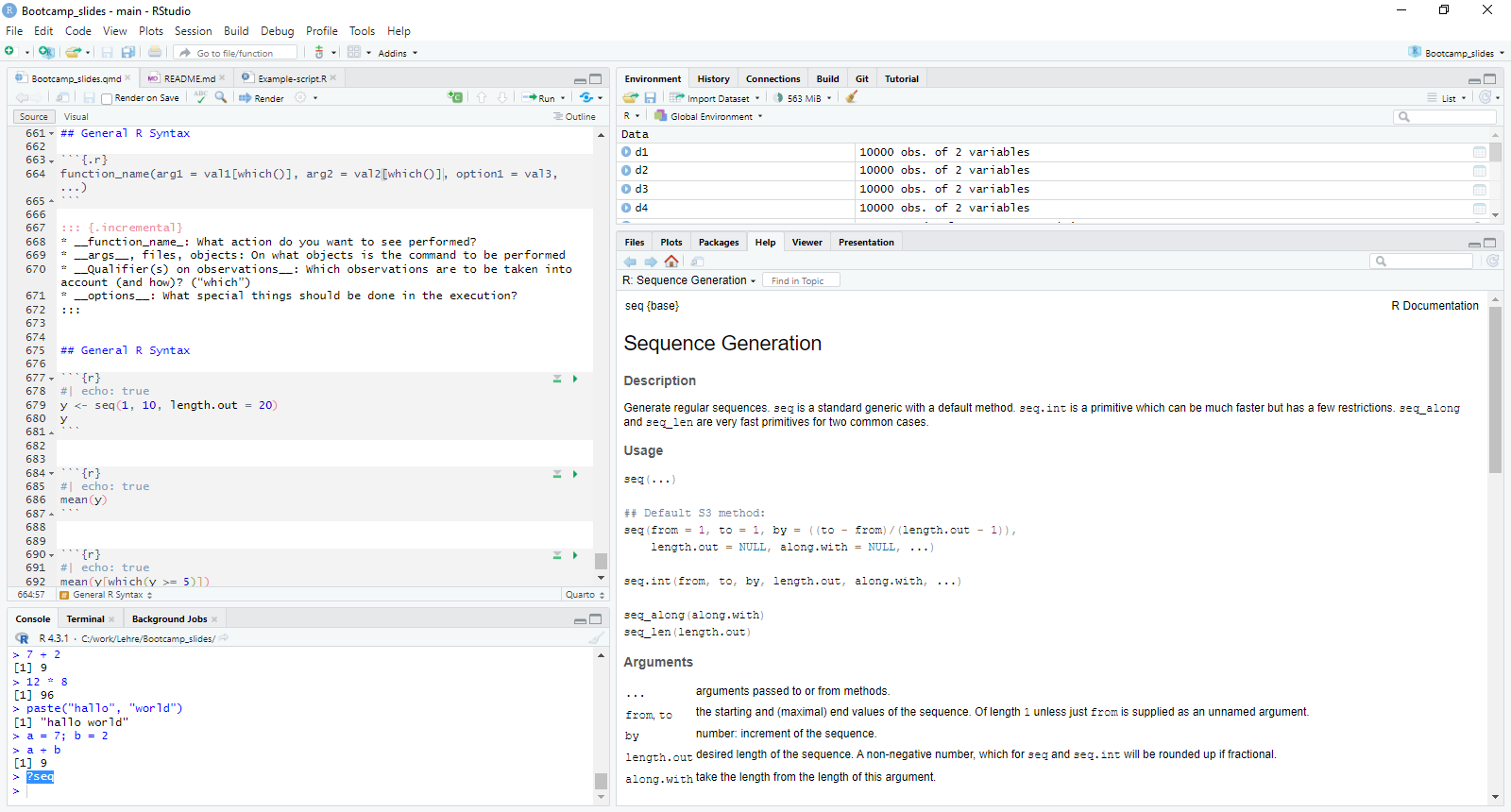

Structure of Commands in R

General R Workflow

- Assign a value to an object

General R Workflow

- Define the objects a and b

General R Workflow

- Perform an operations with them

General R Workflow

- Return the results

General R Syntax

- function_name: What action do you want to see performed?

- args, files, objects: On what objects is the command to be performed

- Qualifier(s) on observations: Which observations are to be taken into account (and how)? (“which”)

- options: What special things should be done in the execution?

General R Syntax

Produce a sequence between 0 and 10 with 20 values

[1] 0.0000000 0.5263158 1.0526316 1.5789474 2.1052632 2.6315789

[7] 3.1578947 3.6842105 4.2105263 4.7368421 5.2631579 5.7894737

[13] 6.3157895 6.8421053 7.3684211 7.8947368 8.4210526 8.9473684

[19] 9.4736842 10.0000000Calculate the mean

Calculate the mean of all values above 5

“?[command]” is your friend

Define your working directory

This is a path: “C:/work/Lehre/Bootcamp_slides/” (look the slash direction)